The 3 Biological Laws: Force Your Muscles to Grow

Walk into any gym, and you will hear a thousand different theories on how to build muscle. "Lift heavy." "Chase the pump." "Confuse the muscle." "Eat big to get big." While some of this advice works, most of it is accidental. The people growing are often succeeding in spite of their programming, not because of it.

But muscle growth—scientifically known as Hypertrophy—is not a mystery. It is a biological calculation. Your body does not want to build muscle. Muscle is expensive tissue; it requires massive amounts of energy to build and even more to maintain. From an evolutionary standpoint, being too muscular is a liability during a famine.

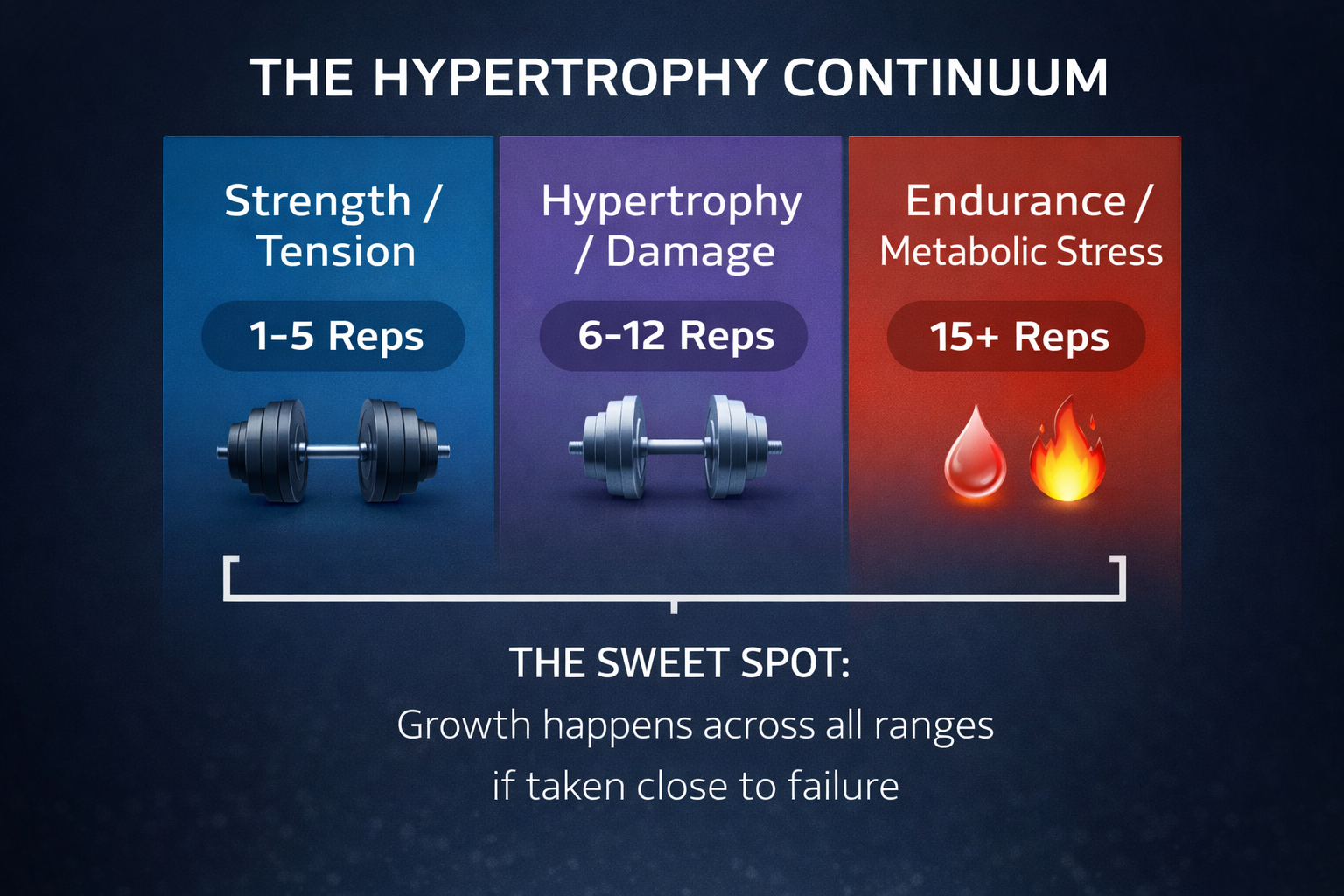

To force your body to build this "expensive" tissue, you must present it with a stimulus so undeniable that it has no choice but to adapt. Science has identified exactly what that stimulus is. There are three primary mechanisms of muscle growth: Mechanical Tension, Metabolic Stress, and Muscle Damage.1

Mechanism 1: Mechanical Tension (The King)

If hypertrophy were a kingdom, Mechanical Tension would be the King. It is the single most important driver of growth. Mechanical tension is the physical force applied to the muscle fibers.2 Think of your muscle fibers like a tug-of-war rope. When you lift a heavy weight through a full range of motion, you are pulling that rope taut.

This tension is detected by sensors on the cell membrane called mechanoreceptors. When these sensors feel a load that threatens to snap the "rope," they trigger a chemical cascade (notably the mTOR pathway) that tells the DNA in the muscle cell nucleus: "We need to reinforce this structure."

How to Maximize It:

Load is Key: You must lift heavy enough to recruit high-threshold motor units (the big Type II fibers).3

Range of Motion: Tension is not just weight; it's stretch.4 Research shows that training a muscle at long muscle lengths (e.g., the bottom of a squat or the stretched position of a fly) creates the highest hypertrophic signal.

Progressive Overload: You must add weight or reps over time. If the tension doesn't increase, the adaptation stops.

Mechanism 2: Metabolic Stress (The Queen)

If tension is the heavy lifting, metabolic stress is the "burn." This is what happens when you do high reps with short rest periods. The veins bulge, the muscle burns, and it feels like your skin is going to tear. This isn't just pain; it's chemistry.

When you train in this style (typically 15-30 reps), you create an anaerobic environment. Oxygen supply can't keep up with demand. This leads to the accumulation of metabolites: lactate, hydrogen ions, and inorganic phosphate.

This chemical soup does three magic things:

Hormonal Surge: It triggers a release of anabolic hormones like Growth Hormone and IGF-1.

Cell Swelling: It forces fluid into the muscle cell (the "pump"). This swelling pushes against the cell wall, which the cell perceives as a threat, promoting protein synthesis to reinforce the wall.

Fiber Recruitment: As the endurance fibers fatigue from the acid, your body is forced to call in the big Type II growth fibers to help out, even though the weight is light.

Mechanism 3: Muscle Damage (The Prince)

For decades, we thought this was the main driver. "I'm sore, so I had a good workout."

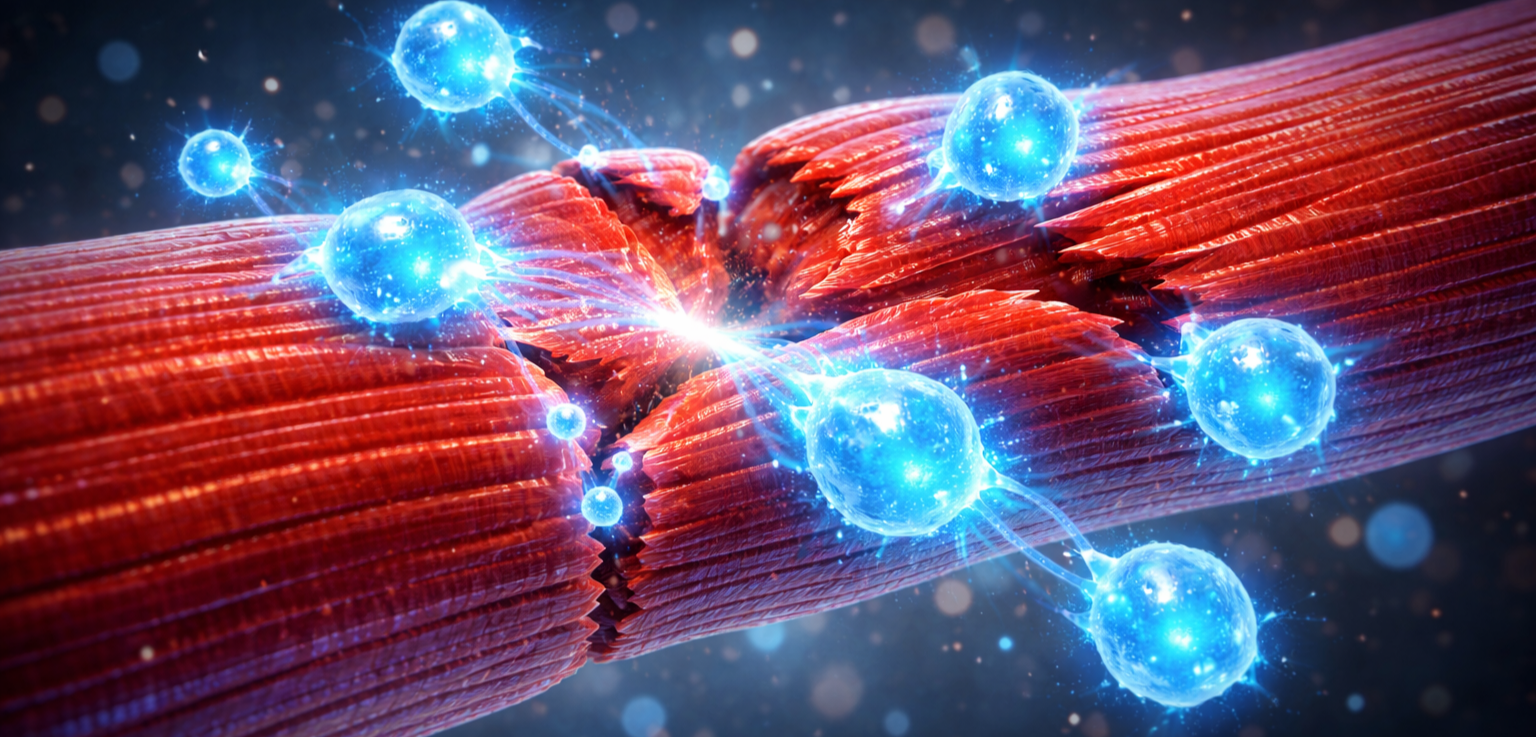

Muscle damage is the physical micro-tearing of the muscle fibers and the surrounding fascia (Z-line streaming). This damage creates an inflammatory response. The immune system rushes in to clean up the debris, and satellite cells (muscle stem cells) donate their nuclei to the muscle fiber to help it repair larger and stronger.

The Caveat:

Damage is a double-edged sword. Some damage is necessary to stimulate repair. Too much damage (where you can't walk for three days) is counterproductive. Your body wastes all its resources just getting back to baseline rather than building new tissue.

Eccentric Loading: Damage primarily happens during the eccentric (lowering) portion of the lift. Slowing down the negative phase of your rep is the best way to trigger this mechanism.

The Synthesis: How to Program for Maximum Mass

So, do you lift heavy (Tension), lift for reps (Stress), or lift slowly (Damage)? The answer is Yes.

A complete hypertrophy program hits all three mechanisms. This is often called "undulating periodization" or simply "smart training."

The "3-Phase" Workout Structure

Here is a blueprint you can apply to any body part (e.g., Chest Day):

1. The Tension Mover (Sets 1-3)

Goal: Maximize Mechanical Tension.

Exercise: A heavy compound movement (e.g., Barbell Bench Press).

Reps: 5-8 reps. Heavy load. Long rest (3 mins).

Focus: Move the weight.

2. The Damage Dealer (Sets 4-6)

Goal: Maximize Muscle Damage via Eccentric Stretching.

Exercise: A movement with a deep stretch (e.g., Dumbbell Flys or Incline Dumbbell Press).

Reps: 8-12 reps. Moderate load.

Focus: Slow down the negative (3 seconds down). Feel the deep stretch at the bottom.

3. The Stress Inducer (Sets 7-9)

Goal: Maximize Metabolic Stress (The Pump).

Exercise: An isolation or machine movement (e.g., Cable Crossover or Pec Deck).

Reps: 15-25 reps. Light load. Short rest (45-60 seconds).

Focus: Constant tension. Do not lock out. Burn it out.

Conclusion: The Science of Effort

While understanding these mechanisms is crucial, there is one variable that governs them all: Intensity. You cannot "tension" a muscle into growing if the weight is too light. You cannot "stress" a muscle into growing if you stop when it starts to burn.

The mechanisms are the map. Your effort is the fuel. Muscle growth is an adaptation to a hostile environment.5 If your workouts are comfortable, your muscles have no reason to change. You must introduce them to the 3 laws—Tension, Stress, and Damage—and force them to answer the call.6

Works Cited

Schoenfeld, B. J. (2010). The mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy and their application to resistance training. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24(10), 2857–2872. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181e840f3

Wackerhage, H., et al. (2019). Stimuli and sensors that initiate skeletal muscle hypertrophy following resistance exercise. Journal of Applied Physiology, 126(1), 30–43. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00685.2018

Krzysztofik, M., et al. (2019). Maximizing Muscle Hypertrophy: A Systematic Review of Advanced Resistance Training Techniques and Methods. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(24), 4897. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16244897

Damas, F., et al. (2018). The development of skeletal muscle hypertrophy through resistance training: the role of muscle damage and muscle protein synthesis. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 118(3), 485–500. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-017-3792-9

Bradfield, J. (2020). Hypertrophy: The Science of Muscle Growth. Human Kinetics.

Suggested Tags

#Hypertrophy #MuscleGrowth #MechanicalTension #MetabolicStress #MuscleDamage #ExerciseScience #Bodybuilding #StrengthTraining #ProgressiveOverload #WorkoutProgramming #Anatomy #Physiology #GymScience #MassBuilding