The Heavy Truth: Rucking Rewires Your Body and Brain

In an era of high-tech treadmills, AI-driven strength machines, and $3,000 spin bikes, the most effective fitness tool might be something you already own: a backpack.

It’s called Rucking (from the German rücken, meaning back), and it is simplicity itself: walking with weight on your back.

For centuries, this was not "exercise"; it was survival. From Roman legionnaires marching 20 miles a day with 60 pounds of gear to hunter-gatherers carrying game back to camp, the human body evolved to carry heavy loads over long distances. Today, modern Special Forces use it as the backbone of their conditioning for a reason—it builds a bulletproof body that is capable, durable, and resilient.

But you don’t need to be a Green Beret to benefit. In fact, rucking might be the perfect antidote to the modern, sedentary lifestyle, bridging the gap between strength and cardio in a way no other modality can.

The Physiology — Cardio for People Who Hate Running

We often view fitness as binary: you either lift weights (strength) or you run (cardio). Rucking destroys this distinction. It is Active Resistance Training (ART), simultaneously building muscle and aerobic capacity.

The Zone 2 Sweet Spot

Most people run too fast to build their aerobic base, pushing their heart rate into the stressful "Zone 3/4." Rucking naturally keeps you in Zone 2—the "fat burning" zone where your mitochondria become more efficient. Because the weight slows you down, your heart has to work harder to move the load, but you don't need the high-impact velocity of running to get there.

Saving Your Knees

Running creates impact forces of 2-3 times your body weight with every step. For a 200lb person, that’s 600lbs of force slamming into the knees. Rucking, by contrast, is low-impact. You always have one foot on the ground, significantly reducing the shear force on your joints while still providing the compressive load needed for bone health.

The Structure — Building Iron Bones and a Steel Spine

Rucking offers unique structural benefits that cycling or swimming cannot touch.

Modern life is a conspiracy to pull us forward: phones, keyboards, and steering wheels hunch our shoulders and jut our heads forward (Kyphosis). The straps of a heavy rucksack physically pull your shoulders back and down. To balance the weight, you naturally have to engage your core and tuck your chin. Rucking forces you into perfect posture. It is essentially a multi-mile corrective exercise for your desk job.

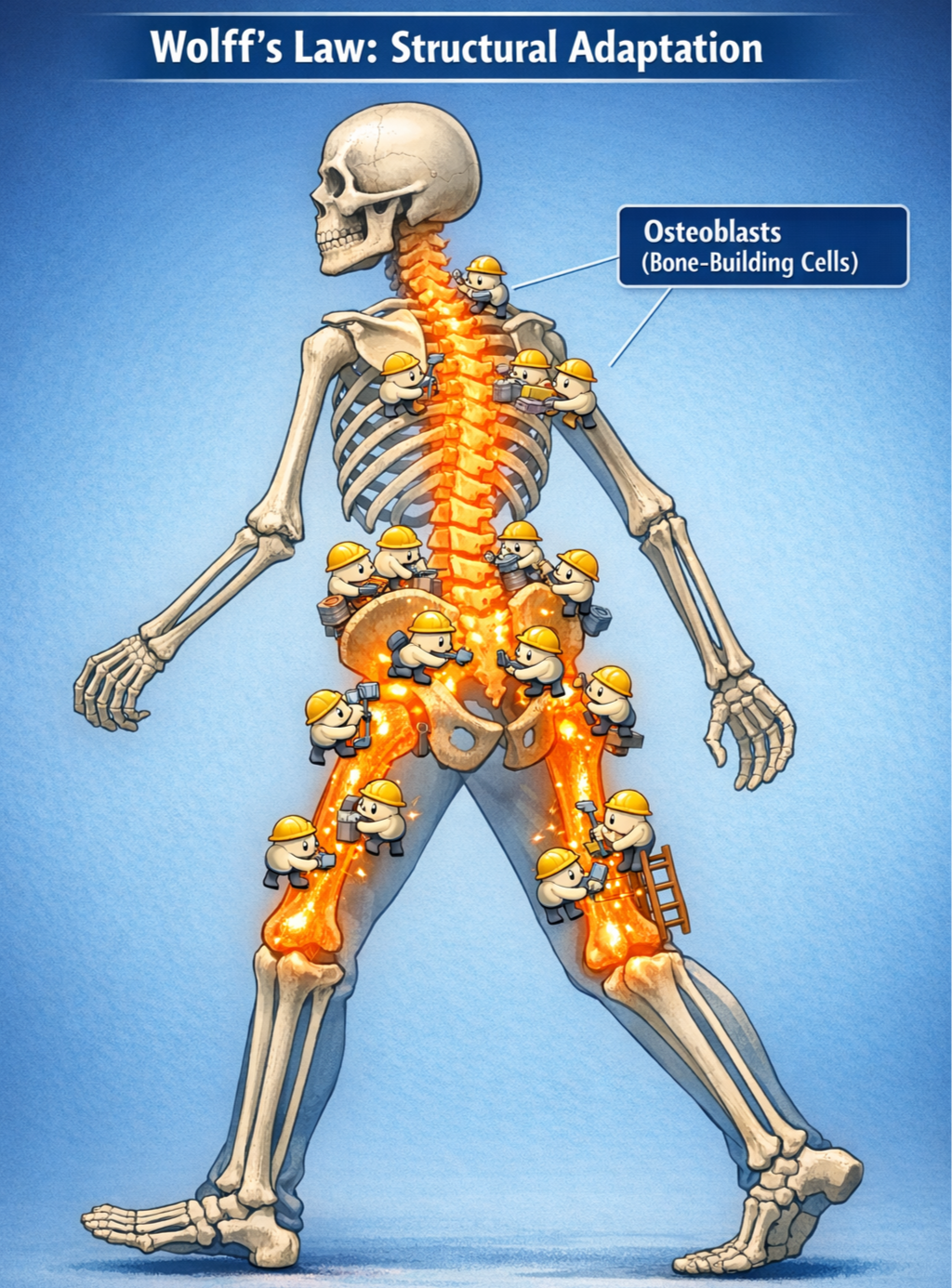

Wolff’s Law and Bone Density

Wolff's Law states that bones adapt to the loads under which they are placed. If you sit all day, your bones become brittle (osteopenia). To build density, you need vertical compression. Rucking applies a constant, manageable load to your spine and hips, signaling osteoblasts (bone-building cells) to lay down new mineral density. It is arguably one of the best safeguards against aging-related frailty.

The Caloric Math

Does walking with a backpack really burn that many calories? Yes.

A general rule of thumb is that rucking burns 2-3x more calories than walking and rivals the burn of a slow jog, without the impact.

The metabolic cost: Moving mass requires energy. For every 1% of your body weight you add to the pack, you increase energy expenditure significantly.

The Afterburn: Because rucking involves muscular resistance (legs, glutes, core, and traps), it creates a larger EPOC (Excess Post-Exercise Oxygen Consumption) effect than unweighted walking, keeping your metabolism elevated for hours after you take the pack off.

How to Start (The Protocol)

Rucking is simple, but do not be a hero on day one. Your muscles may be strong enough for 50lbs, but your connective tissue (tendons and ligaments) needs time to adapt. This is why we recommend the Crawl-Walk-Run Method. Essentially the goal is to not overdue it in the first couple of days and potentially hurt yourself. The CWR method mitigates injury and allows you body to adapt.

The Gear

You don't need a $300 tactical bag to start, but you do need something sturdy.

The Pack: A backpack with thick shoulder straps and, ideally, a waist belt to distribute load.

The Weight: Start with what you have. Wrapped bricks, water bottles, or dedicated "Ruck Plates" (flat cast iron weights designed to sit high against your back).

The Progression

Week 1-2: Start with 10-20 lbs (or approx. 10% of body weight). Walk for 20-30 minutes. Focus entirely on posture: head up, shoulders back.

Week 3-4: Increase distance OR weight, but not both. Go to 30-45 minutes, or add 5-10 lbs.

The Standard: The military standard is often 35-45 lbs. For the average fitness enthusiast, 30 lbs is a "magic number"—heavy enough to stimulate strength and bone density, but light enough to walk briskly without altering your gait mechanics.

Conclusion: Embrace the Suck

Rucking is the ultimate functional fitness. It prepares you for the real world—carrying groceries, children, or luggage—while building an aerobic engine that lasts a lifetime. It turns a simple walk into a workout and a workout into an adventure. So, grab a pack, throw in some weight, and step outside. Your posture, your heart, and your bones will thank you.

Works Cited

Orr, R. M., et al. (2013). Load carriage: Minimising soldier injuries through physical conditioning - A narrative review. Journal of Military and Veterans' Health, 21(3), 31-38.

Knapik, J. J., et al. (1996). Energy cost of walking with loads in soldiers. Journal of Applied Physiology.

Frost, H. M. (1994). Wolff's Law and bone's structural adaptations to mechanical usage: an overview for clinicians. Angle Orthodontist, 64(3), 175-188.

Earl-Boehm, J. E., et al. (2020). The effects of military load carriage on 3D lower extremity kinematics and kinetics. Gait & Posture.

Schulze, C., et al. (2023). Effects of load carriage on the spine: A systematic review. PloS One.